By Bill Kleppel

His Quaker minister father was a successful Main Street businessman with a penchant for outlandish muttonchops. His Civil War hero uncle was a powerful judge, who became a New York State Supreme Court Justice.

So why did Alexander Haviland Gildersleeve turn into such a dastardly, high society reprobate?

The side story, which aligns well with the young Gildersleeve’s lecherous mayhem, is the early onset of trans-continental tabloid journalism, and the public’s insatiable thirst for it. Today, tales of vice, tawdriness, and violence explode into our modern media cycle one day, only to be forgotten in 48 hours… This is nothing new.

Consumption of these sensationalist news stories began to really escalate at the turn of the 20th Century. The advancements in new technologies, along with the proliferation of newspapers in general, helped deliver more content to the masses at an alarmingly fast rate of speed, making the entire world seem smaller. This sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

The exploits of our local boy, Alexander Gildersleeve, is a prime example. Detailed accounts of his crime spree started appearing in newspapers throughout the country. The original events occurred in Chicago in the spring of 1900. It was then covered by many East Coast papers, including the New York Times. An expose with illustrations and interviews from the San Francisco Examiner featured very soon afterward.

Elmer D. Gildersleeve; the Father

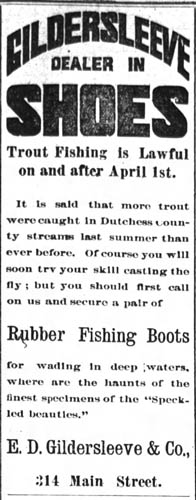

Alexander was born in Poughkeepsie in 1872, to Elmer Gildersleeve and Phoebe (Haviland) Gildersleeve. Elmer, an ordained Quaker minister, was a popular and beloved man about town (as well as being a bit of an eccentric dandy). For years, he ran a successful shoe store at 314 Main Street, first partnering with former superintendent of Vassar College, Benjamin Van Vliet; and then with his son, Elmer Jr. He was also one of the founders of the Poughkeepsie Chamber of Commerce. Elmer was elected the chamber’s first president.

E.D. Gildersleeve & Co. 1891

Elmer was an early automobile enthusiast, and a member of the Poughkeepsie Automobile Club. He played an integral part in building the Fiat car factory in Poughkeepsie in 1909.

Elmer was admired for his work with the Rescue Mission on North Clover Street, and the Vassar Brothers Home for Aged Men. He became an ordained minister for The Society of Friends in 1879, and was pastor of the Friends Church on Montgomery Street. From time to time, he traveled throughout the Northeast and Canada with several religious organizations.

After this mini biography of the elder Gildersleeve, you’d likely envision an amiable, happy, smiling face to go along with his story. In reality, I give you these photos from our Vail Brothers photography collection… Looks can be deceiving.

Elmer D. Gildersleeve Sr.; circa 1870’s Vail Photography Collection

I could’ve fabricated this post by offering these pictures up as Elmer’s deplorable son, Alex, but sometimes truth is stranger than fiction. He was a striking, albeit odd looking fellow (we have even more pictures of Elmer).

Alexander Haviland Gildersleeve; Criminal

Young, charming, and from the “cultivated” East Coast, Alex ingratiated himself into the upper echelon of the new, turn of the century, mid-west privileged class. In the autumn of 1899, William Carpenter Camp, a member of the Chicago 400 society, a group of the social elite during the Gilded Age, met with Alex during a soiree in New York City’s Waldorf Astoria. He was immediately taken by Gildersleeve’s worldly air and manners.

Considering his descendant’s sober and parochial background, Alex was a polished social manipulator, a master name dropper, and quite the actor. He gave the impression to Camp that he was a patron of the arts and a global traveler.

Some of their conversation was published in the San Francisco Examiner.

“I dare say you know London, Paris, and Rome a great deal better than you do Chicago,” said Camp. “You ought to know Chicago. There is a great deal for a young man like you to pick up out there. A great deal.”

“Ah you’re very kind,” answered Gildersleeve. “But the Astor’s are worrying me to stay with them. The Dutchess of Marlborough has asked me over for Christmas in Blenheim (a well-known palace in England).” Alex continued by saying he would like to eventually spend some time in Chicago: “It must be an interesting place, with the pigs and that sort of thing.”

Soon after William Camp returned to Chicago, he was surprised to hear of Alexander Gildersleeve’s arrival in the city. Gildersleeve claimed to have much more pressing engagements. Alex first insisted on staying in hotels during his visit. Yet, he eventually accepted Camp’s invitation to stay at his home with his family.

His continued performance in front of Camp and the rest of the inner sanctum of Chicago’s elite must have been worthy of a standing room only event at the Collingwood Theatre in Poughkeepsie. Alex was invited to parties, dinners, and cotillions, only attended by the moneyed class. Since he’d been anointed as “Billy Camp’s good friend,” Alex was one of the more sought after guests of honor.

He was knowledgeable in many subjects, especially in the interest of jewels. He knew the value and pedigree of priceless gems, from Cleopatra’s pearls to Queen Victoria’s Kohinoor.

One who was particularly allured by these conversations was William Camp’s wife, Edith Schuyler Camp. Edith came from a prominent and wealthy Chicago family, and possessed a rather large collection of jewelry herself. She proceeded to tell Alex everything she knew about her gems… along with info regarding other pieces owned by prominent Chicagoans.

Gildersleeve “exercised an irresistible fascination over women,” which led to many affairs. He stayed in town for months and immersed himself into the layers of Chicago’s social strata, from the highbrow and conservative, to the bohemian and eccentric. He quickly became a widespread favorite in the clubs, hotels, cafes, and bars throughout the city. Alex was ever-present. He always had plenty of money, and time, to spend late into the night.

It all came to a sudden end, when Alex, along with much of Edith Schuyler Camp’s jewelry, had disappeared from the Camp residence. After a few days, many of Chicago’s upper crust began noticing the disappearances of their prized possessions as well. It seemed as if every wealthy family in town was missing something of value.

A large suitcase filled with pawn tickets was found in one of the several hotel rooms Alex was registered under in Chicago. The investigation by local authorities quickly led back to New York City. The Pinkerton Detective Agency found his photo in the New York City Police Departments “Rogues Gallery.” Under the aliases of Thomas H. Smith and H. Gildersleeve, Alex was listed as #6229.

New York City Police Department ‘Rogues Gallery; 1899

Henry Alger Gildersleeve

Judge Henry Gildersleeve; the Uncle

Inquiries with Gildersleeve family members all followed the same lines of conclusion. Young Alexander had been the black sheep of the family. A report in the New York Times claims his father had no connections with him for several years before his foray into Chicago.

Alex’s uncle, Judge Henry A. Gildersleeve, wasn’t the least bit surprised in regard to his nephew’s predicament. “I had a nephew whom I hadn’t seen in the last ten years… His family gave him up years ago.” He continued, “If it is true, I hope he is severely punished.”

Judge Gildersleeve served in the 150th New York Regiment during the Civil War. He fought at Gettysburg in 1863, and also took part in General William Tecumseh Sherman’s March to the Sea in 1864. As well as serving on New York State’s Supreme Court, he was once President of the National Rifle Association.

An unnamed Chicago friend elaborated on how much of a smooth operator Alex was: “He was such an actor that he could gain entrance to any set or class or society.”

“Gildersleeve was certainly a wonder in the confidence line,” claimed Chicago’s Chief of Detectives. From the pawn tickets they found in his suitcase, the chief suspected that, “Tens of thousands of dollars passed through his hands in the last six months." They also found evidence of his schemes stretching further into the cities of St. Louis, Denver, and San Francisco.

William A. Pinkerton (son of Allen Pinkerton, the founder of the famous agency), said he knew Alexander Gildersleeve’s type too well. “He’s a man of education and breeding with a good family name to back him up,” he reflected. “I suppose he’ll escape prosecution in this instance, as he undoubtedly had in many other cases.”

This was, in fact, the case. Alex had several charges against him dropped in the past. He had been discharged after his victims failed to show up to court. Other cases were taken care of behind closed doors. In prior jewel heists, affluent victims of his crimes wouldn’t come forward due to the embarrassment of being taken by a con man.

In this instance, Alex was eventually tracked down and arrested in New Orleans. It was said he’d be transferred back to Chicago for sentencing and a trial. This is where the story essentially goes cold. Mention of his sentencing and possible incarceration failed to make it to the national press.

Aftermath

The questions I have after researching the escapades of Alexander Haviland Gildersleeve remain mysteries. What happened to him? There are no records of him listed anywhere after these stories disappeared from the headlines. He’s not buried with any of his family. Did he change his name? Was he incarcerated somewhere for any period of time? Did he leave the country? How did his life end?

Money can buy silence. And in many cases, money can create silence as well.

Advancements in science and technology have brought out the best and worst in our nature in equal measure. This has remained consistent throughout the 250 years of our nation’s existence. Both positive and negative aspects of our consumption of media have expanded at a furious pace, and there seems no end in sight to it… Should we look at this phenomenon and consciously try to change it? Should we let it run its course, and hope for the best? Do we have any choice? Only time will tell.

References

- “Young Alexander Gildersleeve Social Highwayman and Jewel Thief...” Com, The San Francisco Examiner, 4 May 1900, www.newspapers.com/image/457372026/.

- “E.D Gildersleeve & Co.” Com, The Poughkeepsie Eagle, 30 Oct. 1891, www.newspapers.com/image/114346031/.

- “Swindler Feted in Chicago.” Com, New York Times, 4 Feb. 1900, www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/95958700/94B8E167FAD94148PQ/1?accountid=38287&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers.

- “Death of Elmer D. Gildersleeve Mourned in City.” Com, Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, 21 Nov. 1927, www.newspapers.com/image/114629064/.

- “Alexander Haviland Gildersleeve Social Lion and Clever Thief.” Com, The Sunday Inter Ocean - Chicago, 18 Feb. 1900, www.newspapers.com/image/34341465/.

- “Social Lion and Thief ‘Making Love and Noting Her Diamonds.’” Com, The Chilliwack Progress - British Columbia, 13 June 1900, www.newspapers.com/image/43172522/.

- “Wanted In Chicago.” Com, The St. Louis Republic, 3 Mar. 1900, www.newspapers.com/image/73775484/?match=1&terms=%22Wanted%20in%20Chicago%22.

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. "The rogues gallery at police headquarters" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1899. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6d7865c0-c55f-012f-772b-58d385a7bc34

- “Guildersleeve To Retire.” Com, New York Tribune, 12 Nov. 1909, www.newspapers.com/image/471167689/.

- “Judge Henry Alger Gildersleeve Sr. (1840-1923) -...” Find a Grave, www.findagrave.com/memorial/53201721/henry_alger-gildersleeve. Accessed 16 June 2025.

- “Gildersleeve Under Arrests.” Com, New York Times03, 3 Mar. 1900, www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/95946539/531DC153311B4D6DPQ/1?accountid=38287&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers.